I’d like to start this article with a practical example of psychological safety and diversity that you might well have actually seen (if you’re UK-based), but most probably weren’t aware of.

The actor Ian Puleston-Davies used to play the builder Owen Armstrong in Coronation Street (the world’s longest-running TV soap drama). If you were a regular watcher, you may have seen him standing at the bar, supping a pint and arguing in the Rovers Return pub a thousand times. Or standing in the door of the kitchen in his house, chatting to his family, holding a ‘cuppa’. But always standing, as he has quite a severe OCD about sitting. Two observations if you were a ‘Corrie’ watcher: First, there’s a very good chance you thought Owen was a strong character that added much to the drama but secondly, in all the years he was in the programme, you never noticed he was standing in every single scene!

I chose this example as psychological safety and workplace diversity are hugely interlinked, and we’ll return to the how and why of that soon. Before that, though, it’s worth addressing what Psychological Safety is held to be, in summary, and why it’s important to the safety and health world.

In essence, it’s about feeling comfortable (metaphorically speaking, being able to stand if you really don’t like to, or can’t, sit). Specifically, it’s about being comfortable:

- Admitting mistakes

- Challenging the status quo, raising concerns, and asking difficult questions ..

These are clearly at the very centre of the learning aspect of a strong ‘brother’s keeper’ safety culture, and the third element

- Comfortable offering new ideas (especially if it’s passing bad news up).

This, of course, helps with proactively building a better culture and workplace generally.

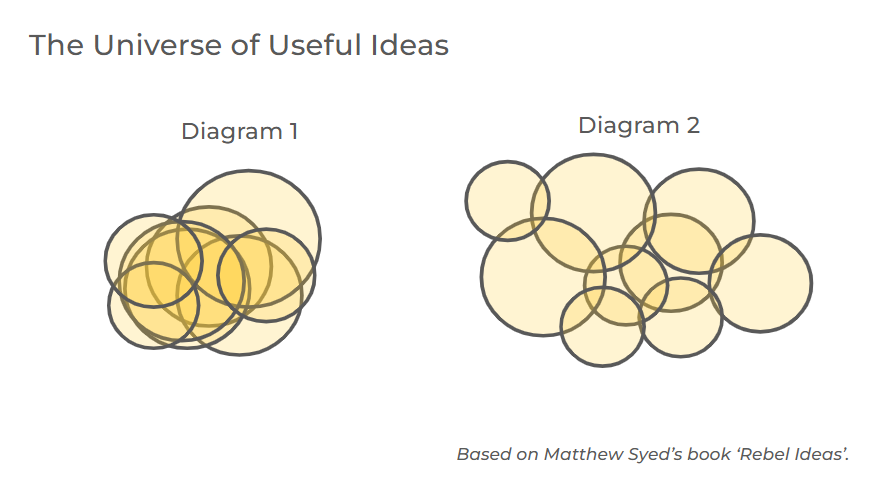

At this point, it’s worth considering two diagrams based on Matthew Syed’s book ‘Rebel Ideas’ about diversity. Syed’s work ranks among the best psychology books for understanding team dynamics and cognitive diversity in organizational settings. Diagram one shows a homogeneous team. There’s a good chance they’ll all get on really well (though ‘boys club’ anyone?). However, diagram two shows at a glance what the limitations of such homogeneity are…

This isn’t just about breadth of experience, background, and worldview. It’s about individual differences, as, for example, dyslexic people can often be very articulate and socially skilled. (Think Richard Branson). People on the autism spectrum can often generate huge efforts and laser focus on specific areas of expertise. (Think Alan Turing, who essentially invented the computer.) In short, they can be fabulously productive and successful in the right role and with the right adjustments and support. Branson comes up with marketing ideas, not marketing copy. Turing designed the first computer, but he’d not have been much use to Apple marketing except as an inspiration for their logo. (Following state persecution for his sexuality, he killed himself by taking a bite from a poisoned apple.)

Health and Wellbeing

Elements 4 and 5 of psychological safety are more squarely focused on this area as, specifically, they involve feeling comfortable:

- Requesting support and/or connectivity

- Expressing vulnerability

In short, it’s not good not to talk, and there are 1001 articles to cross-reference to on this topic.

Why Doesn’t It Happen Naturally?

Because a typical person won’t like change and will instinctively like people who are similar to themselves. The comfort of homogeneity is as natural as the sun coming up. But it doesn’t correlate with organisational excellence as well as a psychologically safe culture does. This will require effort as it’s a truism that if you are not systemically cultivating it then you probably don’t have very much of it! (And a cross reference here to 1001 papers on Heinrich’s Principle of tending to get the luck your planning and efforts deserve).

Here we can also productively refer to another classic piece of safety thinking – Andrew Hopkins ‘Mindful’ safety. If people aren’t telling you about the 1001 problems and issues that they’re facing on a daily basis it’s hardly ever because there’s nothing to say it’s because they’re keeping quiet. This, primarily, for two simple reasons:

- They fear what will happen if they speak up

- They think speaking up will prove pointless anyway …

We’re all read articles or seen films about whistle-blowers achieving great things for their field or even society in general, but ata huge personal cost as vested interests circle the wagons. However, on a day-to-day basis just a bit of frostiness in a canteen – perhaps because colleagues have been made uncomfortable or have been mildly inconvenienced in the short term – can certainly inhibit a potential ‘speaker upper’.

We need, simply, to work to build a culture where “saying something” has more positive than negative consequences. Where we get the support or reasonable adjustments we request. Where management lavishes praise and gets back to you and closes out the feedback loop, so, on balance, discomfort proves relatively less important and a repeat of speaking up is more likely.

First Steps.

The first thing an organisation can do is to take the trouble to explain to staff why it’s important to excellence. Coaching 101, step 1, is to treat people like adults by using data, illustration and reasoning.

Second, make it easy for staff to contribute using specific and resourced methodologies. A simple example from the world of physical safety would be a behavioural project team training in behavioural basics, then asked ‘what goes wrong? why does it go wrong? and what can we do about it?’ From the world of mental health: tool box talks introduced by some data about the sheer incidence of it followed by a little personal testimony (perhaps?) and the question ‘so if any of you are feeling really crap today, for whatever reason .. please say something now, or, if you prefer, pop by my office in a little while …’.

Or perhaps where a claimed ‘open-door’ policy doesn’t in practise come complete with a forcefield or where a meeting closed with ‘any questions or concerns?’ is with a genuine question and not that includes ‘I dare you to push back’ body language. (The later inevitably followed instantly by a ‘no? good!’).

Other simple examples: a team problem-solving sessions where articulating the W (weaknesses) and the T (threats) in a SWOT analysis is actively encouraged. Or a KISS session where keep, improve, stop and start are all systemically worked through with input addressing diversity and psychological safety actively encouraged. (“Ian, the role is yours … you are Owen!” … ‘that’s great but I have one little request that I assure you will save an awful lot of time during filming …”)

Conclusion

Finally, it’s important to cross-reference with accountability. Psychological safety is about striving to make certain behaviours and actions, that may well not come naturally, but which are of benefit to the organisation, possible. It’s not carte blanche to do and say whatever you want…

So, to return to where we started and cross-reference to another great Manchester-made TV programme – the Royale Family. Always standing in a scene because you have a severe OCD about sitting is acceptable because it’s a genuinely workable accommodation. Always insisting on sitting down because you simply can’t be assed to stand up isn’t!

About the Author

Professor Tim Marsh was one of the original team leaders of the research into behavioural safety in the 1990s. Since then, he has worked with around 400 major companies and is considered a respected authority on behavioural safety, safety leadership, and organisational culture.